The lute is one of the oldest musical instruments. Its history spans four thousand years, encompassing Arab, Persian, and Babylonian musical cultures. Imported from the Arabic-speaking world and/or Moorish Spain, the oud (al-ʿūd = the wood), played with a quill, was the precursor to the European lute.

The bent-neck lute with gut frets was in Europe exposed to multiple factors which influenced its centuries-long development from the late Middle Ages to its heyday in the 16th century (with the largest number of lutes and preserved lute manuscripts, approx. 200 prints) and finally to its complete disappearance around 1800. During its centuries of use by the aristocracy, clergy, and emerging bourgeoisie, major changes took place in its value and fashion (Middle Ages - Renaissance - Baroque - Classical). Social upheavals affected all areas of culture, including music: from one era to the next, representative musical and tonal preferences changed enormously. These musical upheavals – “the search for the new” – were driven by competition among the avant-garde of each era. Ever-changing requirements also affected the lute: their area of application changed (polyphony, solo lute, broken consort/treble to bass, ensemble music, song accompaniment, monody, basso continuo in opera, lute concert), as well as playing technique (plectrum, “thumb inside,” “thumb outside” finger stroke), tuning (vieil ton / “Renaissance lute tuning,” accords nouveaux, nouvel accord ordinaire / NAO) / d-minor baroque lute tuning) and the string material itself. Technological innovations made weighted / thinner gut strings for the basses (loaded gut) possible. These factors initiated the expansion of the range of notes on the fretted neck towards the bass. All this led to extensive redesigns of what was a fragile lute into “new constructions” of the time, and to repeated modifications of existing “old, disused” instruments that were suitable for this purpose.

Innovations were not only made to the external form, but also to the central element of sound production – the very thin spruce soundboard and its static substructure made of spruce bars. These transformations are particularly evident in the lute soundboard at the bridge, the center of sound production, and in the different bar arrangements underneath. The static substructure of the lute soundboard in front of the bridge – consisting of continuous crossbaring – was retained, but their number decreased from the Renaissance to the Baroque period.

The lute of the Middle Ages

4- or 5-course lutes from the Middle Ages were played with a quill (plectrum) and almost certainly had no bars under the bridge. No original lutes have been preserved. Their appearance can only be reconstructed on the basis of historical illustrations.

The lute of the Renaissance in “vieil ton” tuning

(fourth – fourth – major third – fourth – fourth = vieil ton)

(e.g. alto lute: g' d'/d' a/a f/ f c'/c g/G 7.f/F (d/D) 8.e/E 9.d/D 10.c/C)

In 1501 Ottaviano Petrucci invented sheet music printing in Venice, which was used to rapidly spread music. In order to enable polyphonic playing, around 1500 the quill was gradually replaced by the thumb-inside finger technique. In the first half of the 16th century, lutes usually had 6 courses in “vieil ton” and most likely had a treble bar under the bridge. This enabled tonal shaping and amplification of the treble register. There are no completely original 6-course lutes or lute soundboards preserved. The oldest surviving lute body dates from 1519 and was built by Matteus Pocht from Arzl near Innsbruck. The first references to an extension of the basses to 7 courses date from around 1490. However, the string material – mostly made from sheep gut – initially limited the diatonic descending extension of the bass on the fretted neck due to its dull sound beyond a certain string thickness. In the last quarter of the 16th century, new technological developments in string manufacturing made it possible to extend the bass. A newly developed type of string with an artificially produced higher density (apparently gut strings enriched with metal powder – loaded gut) made it possible to use a lower string thickness with the same pitch/tension, thereby producing a good sound. Manuscripts and prints document a rapid expansion of the bass register to 7 course from 1574, to 8 to 9 course around 1600, to 10 course from 1611, and finally to up to 13 course during this period.

Parallel to the expansion of the bass register, the development of the bass bar under the bridge began. Shortly before 1600, the lute body with one or two treble bars and a bass bar under the bridge became the general standard in the lute-making center in Füssen, known as the “Renaissance bar” construction. The treble bars enable the tonal shaping and amplification of the treble register. The bass bar serves to promote the overtones (the high sound components), the bass, and to shape the vibration behavior of the bass registers. Due to the significant expansion of the bass register and the resulting “livelier” bass line, the “thumb-inside” stroke was replaced by the “thumb-outside” stroke.

In the Renaissance, the lute was considered the “queen of instruments” and several thousand lutes were produced. From the beginn of the 17th century onwards, the central importance of the lute in music gradually declined. The tonal diversity (of the different instruments) comes to the fore.

The basso continuo lute in the Baroque period in “vieil ton” tuning

(e.g. "re-entrant" Theorbo: a/a e/e h/h g/g d/d a/A 7.G 8.F 9.E 10.D 11.C 12.H’ 13.A’ 14.G’

(e.g. Arciliuti: g'/g' d'/d' a/a f/ f c'/c g/G 7.F 8.E 9.D 10.C 11.H' 12.A' 13.G' 14.F')

Around 1600, a paradigm shift took place. The basso continuo – the thorough bass (ca. 1600-1800) originated in the musical center of the time, today's Italy. It served as a central technique in Baroque music for the accompaniment of the newly developed monody, for the new genres of opera, oratorio and (instrumental) concert. At the same time, a new type of lute instrument began to develop: the theorbo-style thorough bass lute in “vieil ton”, with a varying number of diatonically descending bass strings and a Renaissance bar construction under the bridge. Such changed musical requirements in terms of bass strength and projection were taken into account in the manufacture of the new type of lute. Playing technique also adapted to the new requirements, and from this point on, a distinction was made between theorbists and court lutenists.

Florentiner Camerata Ein Irrtum revolutioniert die Musikgeschichte German.pdf

The lute in the French Baroque period in the “nouvel accord ordinaire” (NAO) / d-minor tuning

(e.g. in d-minor: f' d' a/a f/ f d/d 6.a/A 7.g/G 8.f/F 9.e/E 10.d/D 11.c/C)

Shortly thereafter, a highly experimental phase began in the power center of France. Another paradigm shift took place with the 10-course solo lute and its tuning. Based on the “vieil ton”, the “accords nouveaux” emerged in 1622 with a total of 1,923 surviving pieces in different tunings. From this multitude of tunings, the “nouvel accord ordinaire” (NAO) / d-minor baroque lute tuning (with a pitch of around 392Hz) became established in 1638. The French solo lute that emerged from this upheaval had 11 courses, with the first two courses strung in unison, a treble rider, and a Renaissance bar construction under the bridge. The middle register of the lute gained in importance in compositions and fingerings. The new solo repertoire for the French-style lute – with its scope for expression – spread throughout Europe, except in the region of present-day Italy. This stage of development of the solo lute was also the end of its development in France. Unfortunately, no original 11-course lute from France has survived in complete condition. However, the shape and appearance of French solo lutes from this period can be clearly seen in a number of detailed historical illustrations.

around 1670, Fauchier Laurent - Portrait of a man tuning a lute

Lutes from the Habsburg Empire and German-speaking regions in the Baroque period in nouvel accord ordinaire (NAO) / d-minor tuning

(e.g. in d-minor: f' d' a/a f/ f d/d 6.a/A 7.g/G 8.f/F 9.e/E 10.d/D 11.c/C 12.H/H' 13.A/A')

The French solo lute became established in the Habsburg crown lands around 1660. In the last quarter of the 17th century, due to changing tonal and musical preferences in the Habsburg empire and German-speaking countries, the bar arrangement under the bridge of the 11-course d-minor solo lute (which had been adopted from France) changed once again. Around 1700, the Renaissance bar construction was gradually replaced by a Baroque bar construction with 6 to 7 fan-shaped bars under the bridge; this remained the standard bar arrangement until the lute disappeared around 1800. Apart from the static aspect, the fan-shaped bar allow the overtones (the high-pitched components of the sound) to be shaped, which increased the overall volume of the sound. Around 1700, the French style in the Habsburg empire (Silesia, Bohemia, and Austria) was increasingly infused with cantabile elements. In Vienna, the primary solo use of the NAO lute came to an end, and a new genre emerged: the lute concerto. From then on, the baroque lute was combined not only with its counterparts in different sizes, but also with string instruments as an obbligato lute. In addition to the continued use of the 11-course lute with a treble rider, around 1720 in the Habsburg empire, the basses of the 11 courses d-minor lutes were extended from the 8th course onwards by means of a swan neck, in a ratio of approximately about 2 : 3. Around the same time, the bass was extended from 11 to 13 courses in German-speaking countries. Initially, this was done from the 12th course with a bass rider, then around 1729 from the 9th course with a swan neck in a ratio of about 3 : 4, and finally around 1738 with a triple pegbox “Jauchhals”. This form is also the end of development. The fretted courses specified in the solo repertoire provide information about the type of 13-course lute for which the music was composed. Up to the 8th course, music was composed for a swan-neck lute, and above the 8th course for a lute with a bass rider. The 13-course lute in d-minor tuning – which was now mainly used for the solo repertoire – increasingly became the virtuoso instrument of professional players/composers and reached its peak once again around mid-century. This was followed by a gradual decline in its use in professional music-making. Around 1800, a new paradigm shift began—the stylistic change toward classical music (Away from the overtone-rich sound of the plucked instrument towards the more fundamental instrument). This led to the complete disappearance of the lute, the thorough bass lute, and other chordal instruments.

Changes in playing technique from the Renaissance to the Baroque period

According to historical illustrations in the Renaissance, the plucking hand was usually positioned in front of the sound hole or roughly in the middle of the bridge. At the beginning of the Baroque period, the “thumb-inside” technique of the Renaissance was replaced by the “thumb-outside” technique. During the Baroque period, the plucking hand on solo lutes increasingly moved in front of the bridge – until the supporting finger was just in front of, level with, or behind the bridge. A functional, acceptable tone for a solo lute is only possible with such a close position to the bridge if the string tension is slightly lower.

In the Renaissance, playing on the fretted neck involved a great deal of stretching. In the Baroque period, the style of writing relied heavily on open strings and rarely required stretching. This was a significant change compared to the Renaissance and represented a new style of music which was reflected in the new playing technique.

Changes in the instrument’s surface feel from the Renaissance to the Baroque period

In the Renaissance, the neck cross-section and back were almost straight, lengthwise. During the Baroque period, a strong curvature transverse to the fingerboard up to the soundboard and a concave curvature in the longitudinal section, tapering sharply towards the pegbox, were introduced on the NAO / d-minor solo lutes to aid playing.

The tuning tone

The absolute pitch of the lute in the Renaissance was not initially specified. Contemporary textbooks (e.g., Martin Agricola, 1528) often recommended tuning the highest lute string (pitch) / chanterelle (dm=0.42-45mm) as high as possible—slightly below the breaking point of the gut string. There was no uniform, supra-regional absolute pitch. The absolute pitch, which was decisive for the length of the strings, varied between approx. 370-470Hz in the 16th to 18th centuries, depending on the place and time. (In France until approx. 1700 around 392Hz, in Vienna around 467Hz). In our time, the following tuning pitches have become established: A' 440 Hz for the Renaissance, A' 415 Hz for the Baroque period from 1650 to 1750, A' 466 Hz for the early Italian Baroque, and A' 392 Hz for the French Baroque.

- On solo baroque lutes up to around 1700, the highest lute string / the chanterelle was tuned slightly more as usual below the breaking point.

String material

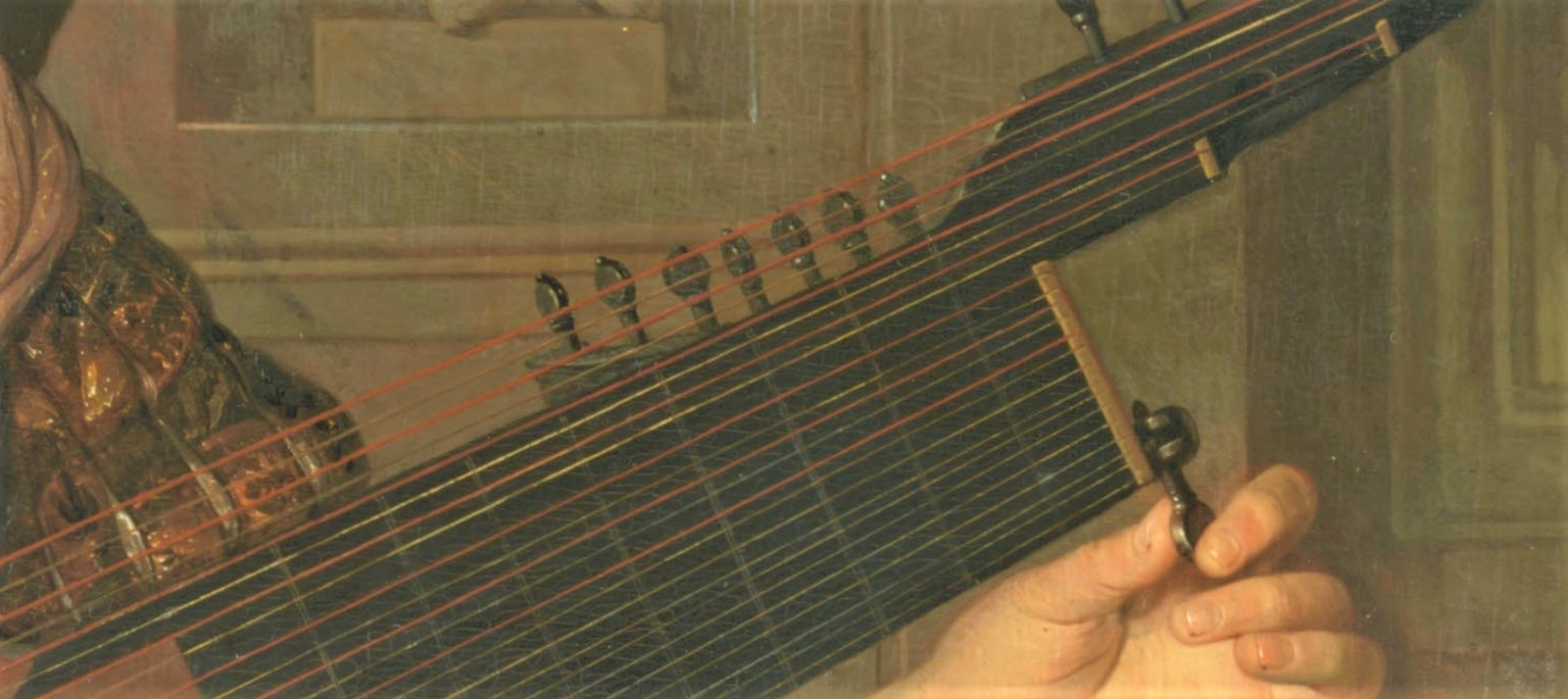

The strings used were mostly made of organic material gut (smallest possible diameter 0.42–45mm). Around 1660, strings with a gut core and half or full metal winding were developed. Due to the different sound aesthetics of the metal compared to the bass strings made entirely of gut with a higher density (weighted), they found little acceptance for lute basses and – according to existing sources – only slowly gained acceptance. Until 1750, red to dark red strings "loaded gut" can still be seen in several historical paintings of 11- and 13-course swan-neck lutes.

Anna Rosina Lisiewska from 1713-1783 - lady with lute

around 1745, Antoine Pesne 1683 - 1757 - Freifrau von Keyserlingk

around 1750, Anna Rosina Lisiewska von 1713 - 1783 - Allegorie des Hörens

No original “loaded gut” gut fragments strings (organic material) from this period have survived, and the exact know-how of their manufacture has been lost. There are several indications for this / a new type of string, how else could the sudden expansion of the bass registers mentioned above be explained. The string manufacturer Aquila is attempting to produce “loaded gut” gut strings and offers the “loaded synthetic string” CD/CDL as a synthetic substitute.

Gut strings produce the best sound on these instruments, but are very expensive and sensitive to moisture and are therefore mainly used for sound recordings.

Lutezine-126-Loaded-strings-paper.pdf

The development of wound strings with silk cores (Cathedral Sound) began in the mid-18th century and only became widespread around 1770. This new type of string heralds the era of the newly emerging single-stringed bourgeois guitar.

String Calculater

Since the 15th century, the lute has been part of the canon of instrument of the upper classes and was considered a status symbol. It had high monetary and symbolic value. Therefore, over time, it was adapted to new musical requirements through modifications.

In the Baroque period, lutes – especially those from the Renaissance (Laux Maler, Hans Frei, etc.) – were extremely valuable instruments. In France, suitable “old, disused” lutes were converted into 11-string solo lutes. In the Habsburg empire and German-speaking countries, “old, disused” lutes were equally highly valued and underwent numerous conversions, first into 11-course instruments and then into 13-course instruments. Where possible, the soundboards were retained during the conversions and only the baring was changed.

(Transformations have occurred repeatedly. In some cases, it is very difficult to clearly identify or date modifications, e.g., shortening strings.)

The entire text is a historical summary of the important developmental phases in lute construction and the design of the soundboard construction without going into detail about fluid transitional forms in transitional periods.

Of course, there were also one or two lute and violin makers during this time who did not want or could not carry out the usual development stages (e.g. fan-shaped baring) on their lutes.

(Information about the design and features of my offered instruments can be found in the instrument groups, individual models and the general terms and conditions).